On Shin Splints and Identity

Advice on diversification, not from your financial advisor

Changes fill my time, baby that’s alright with me / In the midst I think of you, and how it used to be. -Led Zeppelin, Ten Years Gone

My Garmin running watch has been the victim of my frustration on more than one occasion.

Two of these instances in particular stand out. They were almost identical, actually, save for one notable difference.

The first came during a visit to Virginia Beach to see my parents, early in the spring of 2021, when I set out on a run one evening. The goal was modest: two and a half miles of easy jogging. Having dealt with a string of setbacks in my training courtesy of shin splints, I had been very careful in the months prior by gradually increasing my weekly mileage while working on strength and mobility. I was doing all the things the books and articles and Twitter running gurus told me to do. It seemed to be working; I was up to about 20 miles per week without issue.

This two and a half miles was meant to be a recovery run, an easy jaunt just to get the body moving and the heart rate up. Casual. Or at least it was until I got about a quarter of a mile in and felt that familiar shooting pain in both shins. It radiated, burning its way from my posterior tibial tendons up to my amygdala, where it turned into anger1.

I limped back to my parents’ house, walked into the bedroom and hurled my Garmin watch.

After hating it for twenty-eight years, I had fallen in love with running. Once I got past those first few runs where you feel like your heart and lungs are going to combust, I came to understand why it has inspired a sort of religion. I fell in love with the primal act of traversing the earth with my feet, of being absorbed by the symphonic rhythm of my steps and heartbeat. The solitude, the nature, the endorphins: I was hooked.

My body—more specifically, my tibial tendons—did not seem to share this love. Whenever I reached any meaningful amount of weekly mileage, the same pain would return, getting worse with every step. Tibial tendonitis is not the kind of injury you can run through. I have tried.

In addition to trying to run through it, I tried physical therapy, daily mobility work, targeted strength training, dynamic warm ups, post-run static stretches, balance boards, gait retraining, and about twelve different kinds of shoes.

This latest failure to get through a solid week of running without injury wreaked havoc on my psyche. I had put so much into running, and in return I got a recurring subscription to shin splints. I sulked for months, frustrated and dejected by my inability to become a real runner. Other areas of my life suffered.

The second instance of watch-chucking came last week.

A few days prior, I had been in Virginia Beach for another springtime visit. Again, I had a run planned while I was there. But this one was a bit longer. Instead of a 2.5-mile recovery run, this would be a 14-mile behemoth—the longest run of my life, 2 miles longer than the record I had set the Saturday prior.

The setback in Virginia Beach in 2021 hadn’t permanently deterred me, nor had a torn ACL the following year or the countless injuries in between. I was determined to become a runner. I found a coach and a performance-oriented physical therapist toward the end of last year, and together they created a detailed program designed to forge a body that is purpose-built for running.

Having been stopped by the tendonitis so many times before, ‘becoming a runner’ to me means exceeding twenty miles in a week without issue. This was the wall that had continued to prove insurmountable. And it just so happened that this 14-miler would put me right over 20 miles for the week.

I set off through the trails, and, unlike 2021, this run was not interrupted by my tendons. It was spectacular. I ran through the Loblolly Pines and Live Oaks and Wax Myrtles, past the marsh surrounding White Hill Lake, and along the sand of Broad Bay. I ran for hours, and it felt fucking amazing.

It seemed like an incredible turn of poetic justice, conquering my running demons in the same place they had consumed me two years ago. I was sore—so sore—but more than anything I felt triumphant. I was now a runner.

Or at least I thought I was. Still riding the high from the previous Saturday’s 14 miles, I set out last week on a 5-mile tempo run. I felt stiff when I headed out the door, but I didn’t think too much of it. I got through my warm up mile and began dialing up the pace. At around two and a half miles—that vexing distance—I felt the unmistakable, infuriating pain of my tibial tendons lashing out in protest. It was back.

Just like in 2021, I limped back to the house, walked through the door, and flung my watch. A couple years, dozens of experiments, and thousands of dollars later, the result was the same.

Two nearly identical experiences. Two monumental setbacks. Two Garmin-shaped dents in the wall.

Except this time, I got over it in about an hour.

What changed?

—

Diversification is a concept typically associated with boring financial advice. I find it much more interesting, however, when it’s applied to our identities.

Identity is a finicky thing. It’s difficult to define, but I think the first five words of the American Psychology Association's definition—an individual’s sense of self—do a pretty good job.

Our sense of self tends to consciously or subconsciously form around what we deem important. Sometimes this is an active phenomenon, where we care so deeply about something that we shape our lives around it. This might be the case with a musician. Other times, our identities just sort of happen. The most common example of a passive identity is, of course, identifying with work. Our jobs have become the default raw materials with which we construct our identities, so if there isn’t anything else in one’s life that trumps work, it tends to serve as an indefinite placeholder.

Whether we come by our identities actively or passively, gravity and inertia often lead to them centering on a single thing. We’re The Soccer Player; The Programmer; The Mom. This is likely because having a single, coherent identity is the path of least resistance. Dealing with self-concept is a messy affair, and inhabiting a clear, singular identity is an attractive antidote to the ambiguity.

The problem with singular identities, though, is that they are fragile. They serve as a single point of failure, like a network without a backup. This is problematic because entropy is an immutable law of nature. The athlete sustains an injury and can no longer compete; the professional loses their job; the parent watches their child move out and start their own life. The constancy of change to our circumstances and ourselves cannot be avoided.

When your sense of self is heavily tied to one aspect of your life, these inevitable changes are likely to bring about a crisis of identity, an existential shock to the system that can cause lasting damage. We see it all the time. The classic example is the midlife crisis, in which one becomes more acutely aware of their mortality, forcing them to evaluate how they’ve chosen to spend their limited time.

For those whose identity is focused in one area, this heightened temporal awareness tends to lead to a crisis of identity for one of two reasons. The first is that changes to their circumstances or themselves have rendered their identity obsolete, as in the case of the injured athlete or the aging parent. The way they used to view themselves and their place in the world no longer makes sense. As a result, they become paralyzed and confused. There is no clear path forward.

The second cause of identity crisis is the realization that they’ve allowed gravity and inertia to dictate their identity for them. They have lived their lives without intentionality, and their identity has defaulted to their job, or their kid, or their addiction to hentai. Their sudden awareness of mortality reveals to them that they don’t particularly like the identity they’ve found themselves inhabiting.

In both cases, the crisis is largely the result of their identity being a single point of failure. Their previous identity no longer fits, and because there’s nothing to serve as a substitute, the entire system breaks down. Anyone who has experienced a crisis of identity knows how inescapably unsettling it feels. Life seems to lose its narrative arc, and all sense of meaning and purpose disappears. It is a hollow existence, one that can lead to irreparable damage.

—

Some folks, such as Paul Graham, believe that the solution is to reduce our identities, to hold onto them less firmly. I think this is accurate, conceptually; the less attached we are to a single identity, the better. But how do we accomplish this?

I think what Graham is getting at in his piece is essentially the philosophy of non-attachment2, and I believe this is an important part of the solution. Non-attachment requires a fluid relationship with what we hold dear, a loose grip on our sense of self that allows us to see more clearly and offers some protection from changes that might otherwise cause an existential crisis. This is a quality we can cultivate, to some degree, through internal work and reflection.

This solution feels incomplete to me, though. Aside from those who meditate on non-attachment for hours each day, most of us are still going to find ourselves identifying on some level with what we hold dear. This is difficult to avoid. How, then, do we hedge against the inherent fragility of identity?

This is where diversification comes in.

The reason that my injury setback in 2021 was so damaging is because running had come to dominate my identity. At the time I was working in a job I couldn’t stand, I didn’t have any creative projects or personal pursuits outside of work, my family lived across the country, and my social life was stagnant. Running was the only thing I was excited about. Even though I could barely run six miles at a time, the idea of being a runner consumed me; I spent much of my free time reading, watching documentaries, or thinking about running. I was clinging to this singular source of identity, however aspirational or insignificant it may have been, because nothing else in my life inspired a self-concept I was proud of.

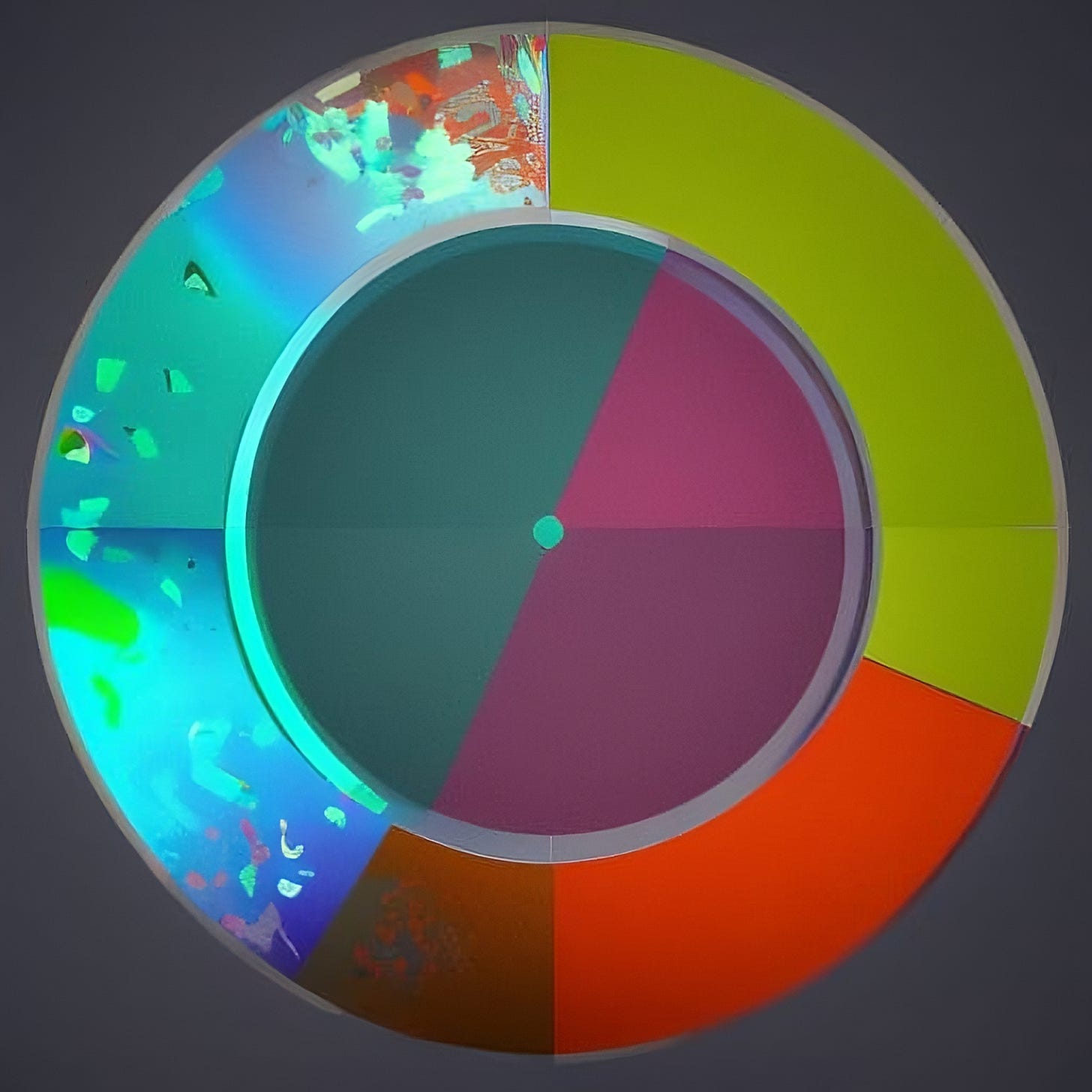

When that 2.5-mile run in Virginia Beach was cut short by the return of shin splints, my identity as a runner took a big hit. And because there was nothing else that could serve as a viable substitute—the pie chart of my identity was comprised of one color, representing 100% Aspiring Runner—the injury set off an identity crisis. I felt lost, unmoored, and hopeless. These feelings persisted for a long time.

Though I still hold the same aspirations of becoming a runner, the 2023 iteration of the Shin Splint Setback did not provoke a crisis of identity. The reason for this has little to do with running. I happen to really enjoy my life now; I live close to my family, I have a lovely girlfriend, I write regularly, I own a few businesses, and I’m on the path to becoming a volunteer firefighter. The pie chart of my identity now contains many colors, each of which are equally important. When one of these identities inevitably takes a hit, be it through injury, a business problem, a personal issue, or simply time passing, it will not shatter my broader self-concept. It sucks, sure—I still really want to be a runner, and hitting a wall at 20 weekly miles for the 47th time makes me want to, well, throw my watch at the wall—but it doesn’t send me spiraling. I have diversified my identity.

It may seem as if this idea of diversifying your identity, of making it larger rather than smaller, is at odds with the philosophy of non-attachment. But I believe it actually helps to achieve non-attachment in a more practical way.

When we diversify our identity, we loosen our grip on any one singular self-concept. Our sense of self can remain fluid by virtue of variety, choice, and context. This prevents the winds of change from blowing us over. We can’t avoid or control entropy, but we can control how we construct our lives. A diversified identity—applied non-attachment, if you will—helps to protect us from the life-shattering potential of inevitabilities like aging, loss, or trauma. It won’t prevent the pain, of course. That’s not possible, nor is it desirable. But it can help prevent that pain from turning into something that causes lasting suffering.3

This all may seem a bit navel-gazey, but the implications are equally significant for our relationships with others. Our fundamentally social nature means that our identities are often intertwined with those around us, either directly through our familial and social roles or indirectly through shared pursuits and experiences. Shocks to our identities have second-order effects. When we’re consumed by our own existential crises—or even simply threats to an existing identity—we are unable to fully engage with, attend to, or, ultimately, love others.

All of this is to say: diversifying your identity is profoundly important work. The work of a lifetime, you might say.

This does not mean we can always avoid crises of identity. They are often a part of growth, and liminal spaces have the potential to be valuable. But, to return to financial terms since the analogy works wonderfully here: we can hedge against the downside risk of existential crisis by diversifying the portfolio of our identity. And then—you guessed it—our lives become richer.

—

I’m thirty-one years old now. I’m starting to find gray hairs on my head and chin, the same gray that now marks most of my twelve year-old dog’s face. The injuries have piled up: I’ve torn ligaments, broken bones, had concussions (seven, to be exact). My body continues to show signs of wear and tear.

My parents have gray hairs, too. Their bodies are showing their own wear and tear. They aren’t getting any younger, nor is anyone else in my family, or yours.

Confronting these truths—the mortality of our loved ones and ourselves—is deeply uncomfortable. This is precisely why crises of identity feel so disastrous. If life didn’t have an endpoint, we would be content with extended periods of floating around without any sense of self or meaning or purpose because there wouldn’t be an opportunity cost.

But life does have an endpoint. Time passes, we change, and our identities no longer fit our new shapes and contours. And when we fail to spread ourselves across different dimensions of life and flavors of existence, the natural shedding of an outdated or outgrown identity can be catastrophic. We lose our sense of self entirely in what is largely, at its essence, a fear of losing time that we will never get back.

A few years ago, the prominent signs of time’s passage in my own life would have likely set off another existential crisis. It is virtually impossible to come to terms with the impermanence of life when you don’t feel good about the life you’re currently living. The profound sadness that comes with confronting the eventual expiration dates of ourselves and our loved ones can only be reconciled by fully embracing4 the limited time we do have. I would argue that a singular identity fails to accomplish this. Having diversified my identity, I'm more content now because I trust that I'm doing the best I can with the time I have.

I haven’t given up on running. The quest to cross the 20-mile weekly threshold continues. I will do my stretches tonight, and the next night. And at some point when my tendons are less angry with me, we will try this running thing again.

But this time, it doesn’t feel like my life is riding on the success or failure of crossing that threshold. I want to be a runner as badly as I ever have, but I’m a lot of other things, too—identities that are equally important to me. If it turns out that for some reason my body is simply not built for running, I will be okay with that. My pie chart has many colors.

I realize that this is not an accurate description of the true neurologic order of operations at play here.

Graham applies this philosophy of identity more within the context of ideologies and dogma, but the implications are equally relevant here.

It’s important to note that diversifying your identity should not be an exercise of ego. The point is to explore identities that you find intrinsically valuable. If you do this for external reasons, it won’t work; identities built for external validation are hollow and fragile, no matter how diversified they might be.

I use the word “embracing” here rather than something like ‘taking advantage of’ because I think the attitude underlying the latter can paradoxically make us more anxious about our limited time because we feel like we have to constantly do. Oliver Burkeman, in his wonderful book 4000 Hours: Time Management for Mortals, makes this point beautifully.

Love the diversification metaphor Alex and the idea that a diversified personality portfolio makes suffering a loss in any life area less painful. I personally recognize the strategy and have used it pretty much as you have described. I'm not sure, however, it protects us against suffering the way you've described, or the way I myself have hoped it might. I have had the experience over and over of keeping myself busy in many domains, with many "irons in the fire," and have found myself not getting to the one thing I am most passionate about, most called to serve at a given time, and suffer as a result of the "diversification." When I finally say "enough" and get down to serving that current singular purpose, the suffering of my self-induced distraction lifts and the more I serve the purpose, the more my identity actually fades into the background, as the work, not my identity, becomes dominant in my attention. As I believe you mentioned, this is complex business, with many tendrils and nuances, requiring a great deal of vigilant self-observation, ruthless self-honesty, not to mention a sense of humor (like keeping track of how many times one's watch has been hurled against a wall) to make it through the labyrinth. The best protection I have found against suffering is to surrender to the most dynamic and engaging work, and if it's all I am doing for a time, and that work comes to end, or doesn't achieve the result that I wanted or hoped for, it's a chance to observe the way I create suffering for myself by investing in future outcomes rather than present process. This is such a juicy topic. Thanks for your thoughts on the subject and for letting me feed back into the conversation. Interested in your perspective, or anyone else with a personal experience in this domain.

This is a great message, and I think hits home for a lot of people. Especially ex-athletes where our identity was just that, athlete. Then we graduated and had to figure out how to hold onto that identity or grow as a person and find a new identity that made us happy. I know it was a lesson that took me a hot minute and several obsessions to figure out