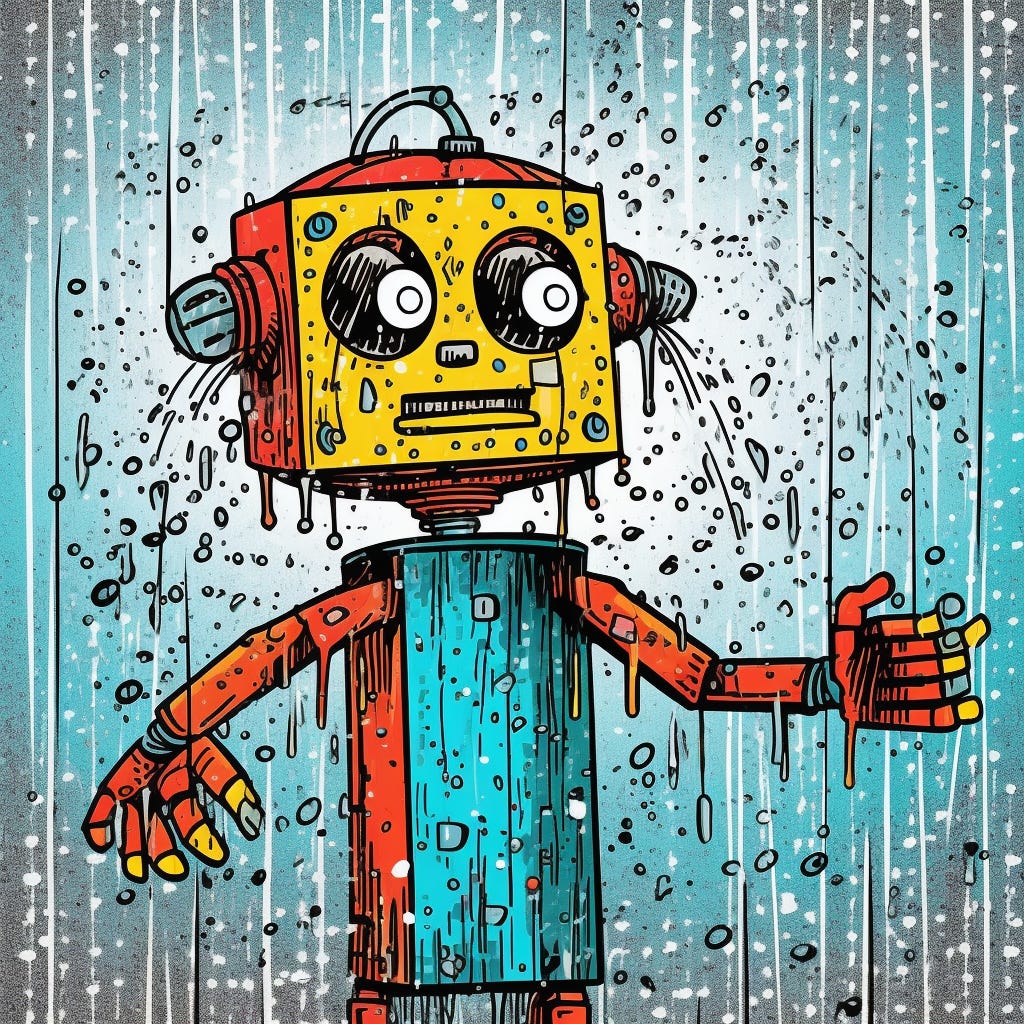

Why Can't We Just Pour Water on the Robots?

A co-written essay

This is an essay I co-wrote with my girlfriend, Jenna, which will either serve as a cute story to tell our friends and family or an awkward monument should we ever break up.

There’s an episode of X-Files where Agents Fox Mulder and Dana Scully face down a sentient, murderous computer—a standard-issue cautionary tale about artificial intelligence in the year 1993. The machine is so advanced that even its developer cannot shut it off. The only way to kill the machine, once and for all, is through a specially-designed virus delivered via floppy disk.

As Jenna watched Mulder and Scully battle the developer and their own government to poison the machine with a virus that only might work, she kept coming back to one thought:

Why didn’t Mulder just…pour a bucket of water on the computer?

The computer was one of those old bulky black Dell towers, with a port for a floppy disk and green-diode letters coloring the ancient cathode ray tube screen. It was decidedly not waterproof.

Jenna couldn’t help but think about all the cell phones she had dropped into puddles or toilets. Those little rectangular computers—exponentially more powerful than the clunky Dell Mulder and Scully were doing battle with—died on impact when they came into contact with liquid. There was no way that Dell was winning a fight with a giant bucket of water.

In 2023, with every fear-mongering article about the next technology or group of people AI will render irrelevant, Jenna finds herself asking the same question.

Why can’t we just pour water on the robots?

Sure, computing technology has evolved since 1993. We’ve got smartphones and clouds and GPTs and all that shit. But all the neural networks and machine learning scripts in the world rely on some kind of physical servers, right? So in the case of a robot revolution or AI reaching the point of murderous sentience, why couldn’t we just round up a bunch of neighborhood contractors and pulverize all the machines with a pressure washer?

William of Ockham, of Razor fame, likely wondered the same thing when he suggested that the simplest answer is usually the most correct.

So why do we seem so intent on building complex viruses to kill all the murderous computers in our own lives? Why don’t we just pour water on them?

—

We tend to assume that the solutions to the problems we face must be as complicated as the problems themselves. This isn’t limited to conquering homicidal computers.

A friend once told Alex a story about a time her sister had an existential crisis. As the shadows grew longer on a seemingly unremarkable day, the sister began to feel distraught.

It started as a vague sense of unease—an unpleasant feeling that something was off, something she couldn’t quite put her finger on. The feeling grew like a tumor. She paced around the house, muttering to herself about college applications and ex-boyfriends.

By sunset the vague unease had become a full-blown breakdown. The sister was sobbing as she took inventory of her life, trying to pinpoint the moment where everything went wrong.

The friend held her sister, trying to console her. She tried talking her down; letting her vent; even a bastardized form of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Nothing worked. The sister was inconsolable.

Then a sneaking suspicion occurred to Alex’s friend. “When was the last time you ate something?” she asked.

“Um…a while, actually. I had a piece of fruit this morning but that was it.”

Ah.

Half an hour later, sitting in front of an empty plate that showed few remnants of the huge meal Alex’s friend had made her, the sister beamed. There were no more tears or questions about the point of slogging through a miserable existence. The energy in the room had transformed.

The source of her sorrow wasn’t a string of poor life decisions. It wasn’t a failed relationship, family problems, or an absence of meaning.

She was just hungry.

—

So what are the origins of our overcomplication? Neither Jenna nor Alex are psychologists, nor do we play them on TV. But we have some thoughts.

Maybe it’s a function of human nature to overanalyze our problems, a byproduct of old survival mechanisms. Many of the problems our ancestors faced were life-threatening. The rustle in the bushes could be a mouse—or it could be a lion. It would have been in their best interest to assume the latter. Most modern problems are more mouse than lion, but, you know, old habits die hard.

Or perhaps we enjoy indulging in the drama of tackling a vast, complex problem. Maybe it entices our egos. Important problems must require important people to solve them! And important people don’t screw around in the sandbox of the simple. Research papers, conferences, coalitions! Attention, adulation, admiration! It’s difficult to recognize or embrace a simple solution when we’re wrapped up in the theater and intrigue of the problem. Throwing water on the robots isn’t likely to garner a Nobel Prize.

It’s also possible that we’ve simply lost touch with our intuition. We’ve placed a premium on cerebral intelligence at the expense of the somatic and instinctual, and while this has spawned an era in which we can fly to space, video chat with people on the other side of the world, and grow meat in a lab, it has also come at a cost: we’ve forgotten much of the wisdom of our forebears in the realm of the intangible, the inexplicable. It could be that our hyperrationality limits us to viewing our problems through a single, intellectually complicated lens.

—

Whether it’s a function of our nature, our hubris, or our rationalism, we have a habit of ignoring the bright orange bucket of water that’s in front of us. Topics like machine learning and human psychology are complex, as are the problems associated with them. But that doesn’t mean the solutions have to be.

Until Jenna’s phone and laptop become fully waterproof—from the inside out—she won’t be hitting the panic button on artificial intelligence and robot domination. If we do face a threat from the computerized overlords in our lifetime, we suggest that the Department of Defense drop Lockheed Martin in favor of the Pressure Washers of America. And wouldn’t you know it—Alex just started a pressure washing business (talk about hitching your horse to the right wagon, am I right?). Folks think he’s doing it for the money or the freedom, but they’re mistaken. It’s about the robots.

Everybody else is trying to play chess. We’re playing checkers.

More co-authored pieces please :)

Alex (and Jenna) -- this was great. Especially loved the insight that we’ve strayed away from intuition. Sometimes things feel right -- or wrong. It’s easy to ignore your gut when you have facts or other data to analyze -- but our genes survived for 10s if not 100s of thousands of years on that very instinct that’s trying to tell you something.

Me, my gut? It’s telling me to have dinner and, after reading this, always keep a super soaker handy.

Great article!