Fiction, and the Two Kinds of Truth

A Swim in the Pond in the Rain

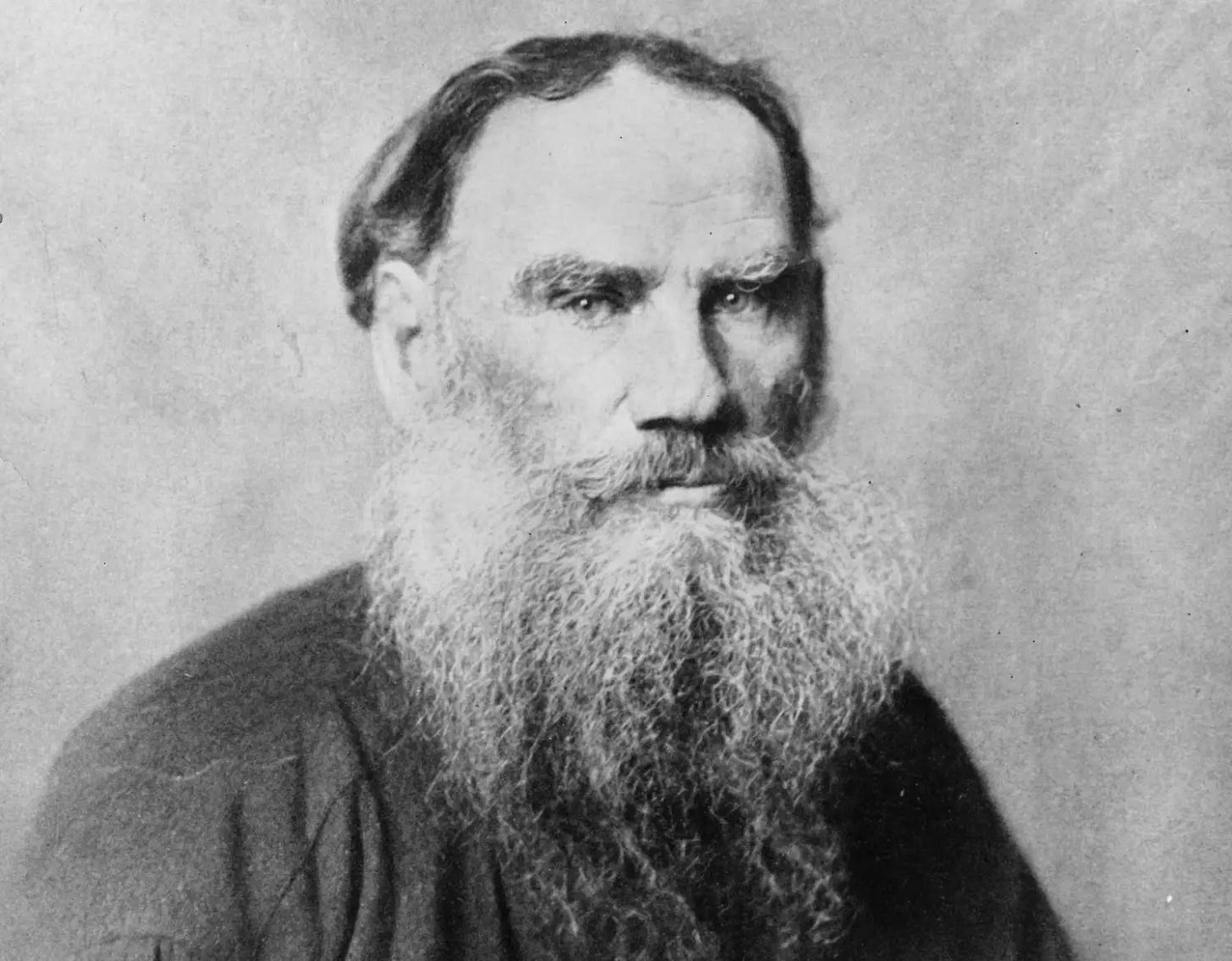

A friend recently recommended George Saunders’ A Swim in the Pond in the Rain, in which Saunders has us read seven short stories by acclaimed 19th century Russian writers (Tolstoy, Chekhov, Gogol, etc.) and then analyzes those stories.

At face value it sounds boring—like one of those college classes you find yourself skipping more and more as the semester goes on. But it’s actually spectacular.

First, it’s accessible: Saunders’ writing makes you feel like you’re hanging out at a coffee shop with a witty, articulate friend who’s crass at exactly the right times. He’s a pleasure to read. More than that, though, he has an absurd talent for taking a story that on the surface seems underwhelming or confusing and revealing elements of that story that leave you in awe of its beauty. And then he takes it a step further—which brings us to the impetus for this essay.

—

As I’ve gotten older, I’ve (slowly, begrudgingly) come to terms with the duality of existence—the paradoxical and contradictory nature of pretty much everything. As desperately as I’d like to stumble upon the thing—a belief system or way of living that is unambiguously correct—it doesn’t seem I’m going to get off that easy. Intellectual truth, much to my chagrin, is contextual, fleeting, subjective.

This is particularly inconvenient for a nonfiction essayist. When I first started writing, I found myself producing a lot of self-help type stuff (which, it turns out, is quite common). You know: neat and tidy thesis, concise advice, clear takeaways. I stumbled upon some interesting insights, but mostly it was just one-dimensional and sterile—empty calories. I was swimming in the shallow pond of intellectual truth.

I eventually realized that I was more interested in tackling the Big Questions—the ones we’ve been diligently working on for some thousands of years that are defined by that pesky duality. But it turned out that my neat and tidy self-help template was not built for the Big Questions. These Questions, I learned, aren’t meant to be tackled so much as courted, or danced with, or lovingly gazed upon. You can’t walk up to the prettiest woman in the room, introduce yourself, then tell her you’d like to date for a year and a half, get married, and have three children in a suburb outside of Chicago. The situation calls for a lighter touch.

This is why I’ve gravitated towards memoir: it seems to be more interested in the Big Questions. When done well, it reports on life through the lens of a perceptive, thoughtful observer without making explicit claims one way or the other. It eschews cheap intellectual truths in pursuit of something greater.

But fiction, until recently, still felt like a foreign land—one I didn’t have much interest in exploring.

—

So, back to Saunders. When I say he takes it a step further, what I mean is that he connects these stories—stories including one where a peasant wins a singing contest, and another where a woman rides in a cart for a few hours—with the Truths they (very) subtly convey. I don’t mean intellectual truths like ‘abortion is good/bad’ or ‘protein is good for you/bad for you’, but rather real Truths, like, ‘we are complex creatures who are simultaneously capable of the most divine good and insidious evil.’

In Saunders’ mind, the reason fiction is so well-suited to convey these Truths is that it allows us to take contradictory fragments of ourselves—the part that is for abortion and the part that is against it, for example—and manifest them as different characters, allowing each of those characters to make a compelling case for their position through the entertaining, indirect vehicle of story. The reader is then able to absorb the Truth of this duality and nuance—of the duality and nuance of everything—through the sneaky, often more resonant pathway of story, one through which we’re wired to receive.

I found this to be pretty profound.

Though the book gave me a fresh perspective on fiction, writing it still seemed out of reach. But last week the perfect storm occurred: I’d just read a particularly delightful part of A Swim, I was bored during an airport layover, and I was tired enough to be disinhibited. I saw a strangely dressed Guido walk by, and, suddenly, I found myself typing an opening sentence:

“It was in Terminal B outside of Gate 24 at LaGuardia Airport that our protagonist, an off-brand Jersey Shore cast member type named Tommy DeVito, stumbled upon his divine purpose in this life.”

From there I just kept going. There was no premeditation behind any of the words that appeared on the page; each sentence seemed to just emerge from the one prior. Since that opener, the story has gotten increasingly ridiculous. But it also seems like it might have something to say—including perhaps, dare I say, the tiniest glimpse of Truth. To use Saunders’ words: the story has started to “tell me what it wants to be.”

This has been a fascinating process, not to mention fun as hell. It’s sort of like the writing I’ve done in the past, in that I’m using words as bread crumbs that will hopefully lead to something interesting. But mostly it feels like an entirely different exercise. I’ve never used this muscle that imagines characters and events and then has them interact in some meaningful way without any idea of where it’s going. And I’m kind of loving it.

I don’t know if I’ll share the story, or what percentage of my future writing will be fiction, if any. There’s no neat and tidy thesis here—well, besides my casual rediscovery of the paradoxical nature of Truth and the multitude of ways we might try to (lightly, playfully) engage with it. Oh, and that those Russian writers are acclaimed for a reason.

I am already in love with Tommy DeVito and can't wait to hear more about you . . . er . . . I mean him.

Fiction, many times, is merely a fantasy of Truth.